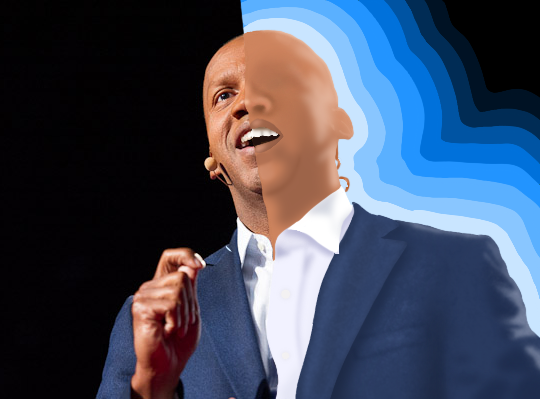

Bryan Stevenson: The lawyer

March 2, 2022

Bryan Stevenson is the twenty-first person from the United States to win the Right Livelihood Award in 2020.

Bryan Stevenson’s career was not in music or design but in law. His career pioneered a defense for those incarcerated and chastised by society. Stevenson portrays this story in his autobiography and a major motion picture, starring Michael B. Jordan, Just Mercy.

After graduating from Harvard, Stevenson headed to Alabama to defend the wrongly condemned or those not afforded proper representation. In his fourth year working for the Southern Prisoners Defense Committee (SPDC), he is assigned Walter McMillian’s case. McMillian is on death row in Alabama, where Stevenson often works because the State lacks a public defender.

McMillian started a prosperous lumber business in the 1970s despite lacking a formal education. His business caused suspicion among the white community. He had an affair with a younger, soon-to-be-divorced white woman named Karen Kelly in 1986. Their relationship led to a child custody battle between Kelly and her husband, in which McMillian testified. His reputation suffered from his involvement with Kelly. At the time, southern states voiced extreme disapproval for interracial relationships.

After McMillian’s court appearance, a white college student, Ronda Morrison, was murdered, and police could not determine the perpetrator. Ralph Myers, an ex-criminal, made a statement to police that he, McMillian, and Kelly killed Morrison. There was extreme pressure to close Morrison’s case. Even though Myers did not know McMillian and there was no evidence that McMillian was involved in any murders, the police accepted Myers’ story.

Since Myers’ story about the events surrounding Ronda Morrison’s murder made little sense, law officers found Bill Hooks, a jailhouse informant. Hooks corroborated McMillian’s involvement by saying he saw McMillian’s truck at the location of Morrison’s murder. Law enforcement finally charged Walter even though he had an alibi on the day of the murder: He spent that day at his home with family and neighbors.

Myers and McMillian were placed in pretrial detention on death row, an illegal move.

Stevenson receives a call from Ralph Myers asking him to visit. Myers admits that he lied about McMillian’s role in Ronda Morrison’s death. Myers also noted that numerous law enforcement officials coerced him into giving false testimony. Myers says this in a trial under oath, perjuring his previous testimonies.

Alabama District Attorney Tom Chapman dismisses the idea that racial bias played any role in McMillian’s prosecution. Stevenson later finds out that Chapman ordered a new investigation into Ronda Morrison’s murder. Agents from the Alabama Bureau of Investigations determined that Walter had nothing to do with her death. Stevenson and the Alabama Bureau of Investigations learn that they identified the same suspect as Ronda Morrison’s real murderer.

Stevenson calls District Attorney Chapman. Stevenson says that he will file a motion to dismiss all charges against McMillian, which the state joins. The court dismisses all charges against McMillian, and he walks free.

McMillian is one of 135 wrongfully convicted prisoners that Stevenson and his team have gotten released from prison. Stevenson and his team, the Equal Justice Initiative, have also garnered relief for hundreds more of the wrongfully convicted or unfairly sentenced.

With his story out for the world to share, Stevenson praises one of his messages:

“The true measure of our character is how we treat the poor, the disfavored, the accused, the incarcerated, and the condemned.”