On fictional fighting felines, and the flaws of cringe culture

‘Warrior Cats’, a 2003 book series, is often seen as “cringy” due to its young target audience, but in reality it has fans of all ages.

A couple years ago, I was in an animation class, working on projects that have ultimately been forgotten. While waiting for the computer to boot up, I pulled out a freshly-printed copy of River of Fire– which had been the newest release in the “Warrior Cats” book series at the time, and began to read.

The kid next to me curiously eyed the bright orange hardcover, which was adorned with a pair of tabbies fleeing a forest fire. “What is that?” they asked, trying to read the book’s blurb.

“Oh,” I said dismissively. “It’s a ‘Warrior Cats’ book.”

I had tried to be discreet, but the effort ultimately failed. “Who the [expletive] here still reads “Warriors”?” sneered a student two rows ahead of me, her eyes alight with disgust. There were dry snickers from the front- a teenager, reading a children’s series? How preposterous! How laughable! A jester before their court! The feeling of mockery stung at my fingertips, but in the end, it was business as usual.

And so, my complicated relationship with Erin Hunter, their books of practical cats, and my cringe-inducing love for the series continued.

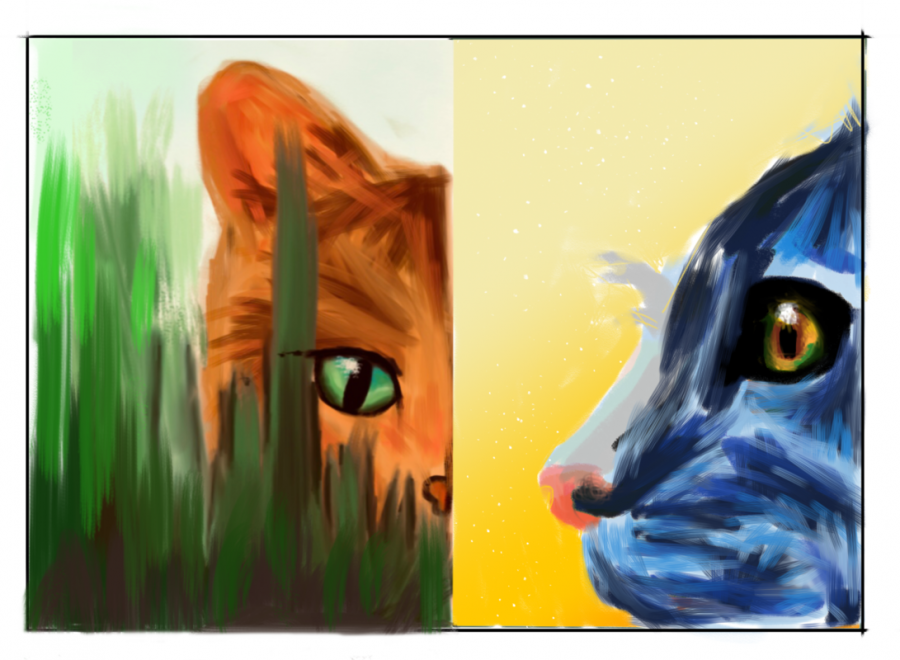

“Warriors”, or “Warrior Cats” as it is more commonly called, is a series of children’s novels by a team of authors writing under the pen name Erin Hunter. The books center around warring factions of cats that live in a forest, and the conflicts that happen between these factions for generations on end. Despite the target audience, the plots of the books are very child-unfriendly; murder and mayhem dapple the pages of Hunter’s feline fantasy. Currently, there are over 100 “Warriors” books, with more on the way.

However, as it stands, “Warrior Cats” is a children’s series. By the time one enters high school, “Warriors”, and the rest of the world of children’s novels, are meant to be shed like adderskin and forgotten in a hazy, nostalgic blur. The issue now with my love of “Warriors” is not anything to do with the books themselves. It is to do with how I am seen when I mention them.

And here is where we come to the core problem at hand- cringe culture.

Caleb Clark, writing for StudyBreaks.com, describes cringe culture: “generally refers to a mockery of groups or activities that are harmless, awkward and/or too earnest… Targets exist on a spectrum from more innocent fun like cheesy performances and bad newscasts to more pointed jeers at groups like feminists. Especially popular subjects include celebrities, furries and TikTok users who take the app seriously.”

Teenagers are especially poised for this kind of mockery. Not only did our generation of teens grow up with shows that often relied on cringe for comedy like The Office and Modern Family, but the cringe phenomenon is often directed at socially-awkward scenarios, which makes for a rocky explosion when combined with the strong social pressures for teenagers to blend into the crowd.

To take the heat off the constant need to blend in, teenagers often turn to others as a point of mockery. Sure, I may struggle with this, but at least I am not that person. Thus, those who do not conform, whether that is because they have interests considered age-inappropriate, or poor social skills, or act in ways that seem unfounded and bizarre, are often mocked and put down upon by their peers.

Warrior Cats is a children’s series, so many of its fans are children who are not as socially aware as teens and adults. The fans who are not children are enjoying a book series meant for children. This makes the series and its fans a prime target of cringe culture. A quick search on Google for “warrior cats cringe” fetches 1,760,000 results.

The cringe response is an evolutionary feature. Cavemen, if alone, were far more likely to die than they were when with their peers. Our brains therefore evolved to encourage conforming social behaviors while discouraging behaviors that might alienate oneself from the crowd, out of the fear of being alone. It is, in fact, based on an empathy response (meaning our brains emulate what the person we are seeing is feeling): Our brains recognize the embarrassment on behalf of the embarrassing person, and we feel it for the embarrassing person.

Aditi Murdi, writing for The Swaddle, sums up exactly what goes on in our heads when we cringe at something. “An empathy response involves the necessity of experience — one cannot cringe without knowing what an embarrassing situation feels like. Now, the contempt or compassion involved in this empathy response is dependent upon the personal experience of the person experiencing cringe, and how they process embarrassment. Cringe content exists exclusively for people to laugh at, or feel contempt for.”

What does this mean? When we cringe, we are feeling the emotions that we would feel if we were in place of the unappealing person. So when we feel contempt or mockery for that person, as is the case in cringe culture, it means we would feel the same contempt towards ourselves if we were the embarrassing one. So, in reality, that feeling of mockery is self-hatred and insecurity in disguise. Instead of dealing with our own self-loathing and insecurity, we choose to project it onto other people, and in the process it becomes a vile sort of “fun.”

Many of these insecurities and feelings of scorn are further propelled by societal bigotries we may not even be fully aware of. Consider, for example, how many television shows and movies use the idea of a man wearing a dress for comedy. Why are we often meant to laugh in these situations? This instills in us the idea that men wearing dresses are to be laughed at and mocked, and that if we ourselves are men wearing dresses, we too should be mocked. So, when we see a transgender woman, especially one that doesn’t ‘pass’ as a cisgender woman, we may be prompted to cringe at them and mock them.

It extends to other bigotries, too. How many times are we presented with a character who is stupid or “not right in the head,” and are meant to laugh at them? How many times do we internally think “well, I do not want to act like that, people might think I am disabled?” How many times do we encounter these feelings of disgust, all of which find their root in bigotry and the fear of someone unlike ourselves?

I myself am autistic, and I feel that I have faced bullying because of it. If you were to ask those who bullied me if it was because I was autistic, however, they would tell a different story. They would say that it had nothing to do with me being autistic. Instead, they would say, it was because I was too loud, or did not have good social skills, or had weird interests that I talked too much about, or because I did not have strong physical skills. All of these traits are, after all, common denominators in cringe culture. But the issue is that all of those things are traits that stem directly from my autism diagnosis. Autistic people cannot control how loud our voices are as well as our neurotypical peers can. We tend to struggle with social skills. We have specific interests that we are deeply passionate for and often cannot control, resulting in often unusual fields of interest. (One of those interests, for me, is Warrior Cats.) We tend to lack the physical coordination that our neurotypical peers master. We are trained from a young age to fear and mock these traits, because they are different from the norm stem from a condition that is frowned upon by society. That is the thing about cringe culture. It does not explicitly target marginalized communities, instead, it targets them in all but name.

However, the feeling of contempt is not inevitable. While we will always cringe at things we find embarrassing, we do not have to respond to it with disgust. Remember, when you cringe, you are feeling what your brain thinks another person should be feeling. So what if you learn to stop fearing standing out? What if you learn to become unafraid of disgust from your peers and unafraid of embarrassment? The feeling of contempt will instead be replaced by a feeling of compassion.

Murdi, again writing for The Swaddle, tells of an alternate response to secondary embarrassment: “Cringe as compassion is when our response to something ‘cringeworthy’ is a memory of one’s own failure. A person who wishes they were treated better in their moment of shame, will view others’ failings with compassion.”

In other words, it is no longer the feeling of “I should be punished if I did this,” but rather “I would want to be treated better if I did this.” Again, to get to that point requires one to no longer fear of being embarrassing or “cringy”. It looks like a daunting task- but remember, many people have the choice of either being considered embarrassing, or no longer being themselves. What we need to do is lose that fear of standing out and looking strange.

Perhaps we should look at “cringy” people more closely. Are they truly being cringy, or are they having the courage to live as themselves in a world that discourages it? Are they truly being weird, or are they being weird by someone else’s standards? Perhaps we should not look at them as targets of mockery, or oddities to gawk at like a circus sideshow. Perhaps we should venerate them. For in a world that is trying is best to conform, to not draw attention, to blend in, they reject that fate. Their unique perspectives and inability to be tethered by the world of compliant social structures means they often will have ideas beyond our wildest dreams. And so, I will gladly proclaim my love for an (admittedly badly-written) children’s series, because there is something much more freeing in admitting that than trying to blend into a world that will, regardlessly, never truly accept my autistic self as an equal.

“Warrior Cats”, in fact, built itself up from this idea. The books start with a housecat wandering into the woods. He is adopted by one of the clans of cats who live there, even though they generally keep to themselves and reject outsiders. Immediately, he receives scorn for his differences. He does not think like they do. He is not aware of their social structures. He often embarrasses himself in front of the other characters because of it. They often regard him with disdain in return. But he goes on to be Firestar, the prophesied savior of the forest, who saves all that the cats have ever known time and time again.

Cats, as a species, do not care for how they are seen. They only care for the people and objects they love, and their safety. They are honest, but not overly unkind. Cats are similar to us- but they have the courage to be themselves, regardless of the household around them.

Ursula is the copy Editor and perspectives reporter for the Stampede, although previously they were known for regularly providing commentary on the site...

Ayaana Pradhan is a senior and this is her third year on the Stampede. Now the print Editor In-Chief, she loves drawing and anything that involves graphics...

Flicker´Pelt • Mar 10, 2024 at 4:27 pm

Oh my . . . This is just plain sad – Warrior is and was my childhood and I will always have a love for the action packed series about the brave , bold , and evil cats of the forests in the Erin Hunter teams fantasy . .

Celia Garcia • Jun 20, 2023 at 11:18 pm

I am 61 and I love these books and have NO children or grandchildren. “Cringe” be damned!!

Dereann • Feb 9, 2023 at 9:41 am

I don’t care if Warriors is a child book! I still love the series and it’s not anyone’s business to get involved and tell me what I can’t read! You should feel free to read whatever you choose no matter your age!

Cacey Rollins • Feb 6, 2023 at 9:20 am

Thank you so much for this perspective. As someone who isn’t as familiar with the meaning of cringe it was enlightening. Our 7 yr old has led the way for our family to fall in love with the Warrior cats. Even 70 year old Grammy is reading them. There’s no age limit on a great fantasy world.

Elisabeth • Jan 9, 2023 at 11:40 am

Good points.But warrior cats is not cringe.I am a (probably) autistic warriors fan so could relate to this well.

_-Lilacpath-_ from Scratch • Oct 15, 2022 at 8:16 am

This is not true, Warrior Cats are not cringe

Isabel Ann Bowen • Apr 21, 2021 at 3:23 am

I learned a lot from this text. Thank you for writing it.

Jayclaw • Jan 18, 2021 at 2:16 pm

I don’t have autism, but yeah I loved these books when I was younger (8-14) and they will always be near and dear to my heart. I’m tempted to read some of the newer ones that I haven’t yet because I feel the social pressure and convince myself it would be “weird” or something, especially as a guy sometimes I remember back in the day reading these books in bed late at night or on long car trips or staying up with my iPod touch under the covers (I wasn’t supposed to have it up in my room at night) and browsing warrior cats forums and watching fan animations. It makes me want to cry in a sense I wish I could go back to those moments, I’d love to go back and read them maybe visit the lake territories one last time but I just can’t get myself to do it because I’m a grown man now and I can’t get over the “cringe culture” I feel forced into.

An autistic whose special interest used to be warrior cats • Dec 26, 2020 at 6:56 pm

I very much enjoyed this wonderfully written article. Warriors, my special interest from ages seven to thirteen, will always be special to me. I think your analysis of cringe culture is correct. The immediate allistic (non-autistic) empathy response is one of cognitive empathy – ‘how would I react if I were in that person’s situation?’ Thus, projecting the observer’s imagined response onto the person in question. This is all right when it occurs between two allistic people with similar experiences because the observer’s imagined response is likely similar to the other person’s actual response. But the method collapses when the two people have had different experiences, or think in a completely different way – an allistic person using their cognitive empathy response on an autistic person is often wrong.

It does make me wonder if this may be a core feature of a perceived social blindness in autistic people, given the findings that autistics communicate just as well with other autistics as allistics do with other allistics. Perhaps that is why autistic people such as myself tend to fail theory of mind tests – I could perform the cognitive empathy response, but from a young age – when allistic children learn that other people respond to situations the same way the allistic child would if that happened to them – I learnt that my cognitive empathy response was almost always wrong (other people reacted in a very different way than I did to the same situation) and therefore useless. So I stopped applying it. When given theory of mind tests such as the marble-in-a-box test*, my reaction is that I can’t answer the question because I do not know what information the puppet looking for the marble does.

*The Sally-Anne test is a scenario usually enacted with puppets, in which the first puppet, Sally, places a marble in a box, and leaves the room. The second puppet, Anne, puts the marble in her (Anne’s) basket. When Sally returns, the question asked to the person being tested: Where will Sally look for the marble?

Nothing But a Warrior • Nov 24, 2020 at 9:37 am

When someone says “You reading WARRIOR CATS? That’s so childish!” (which n one ever said to me)

9If someone ever says that to me) I will say: “Okay then. I guess cats ripping out the guts of each other and surviving in the wild and fighting undead spirits and romance and warrior codes are childish, according to you.”

Bonnie M • Nov 9, 2020 at 2:20 pm

Ah yes, i do agree, cats fighting eachother to the point of getting their guts out and dying is totally targeted to children, those teenagers just didn’t see quality series leave them be

Anthony B • Oct 5, 2020 at 8:07 am

“band kid” tiktoks, if youve seen them, are another example of just making fun of autistic traits. for having special interests especially