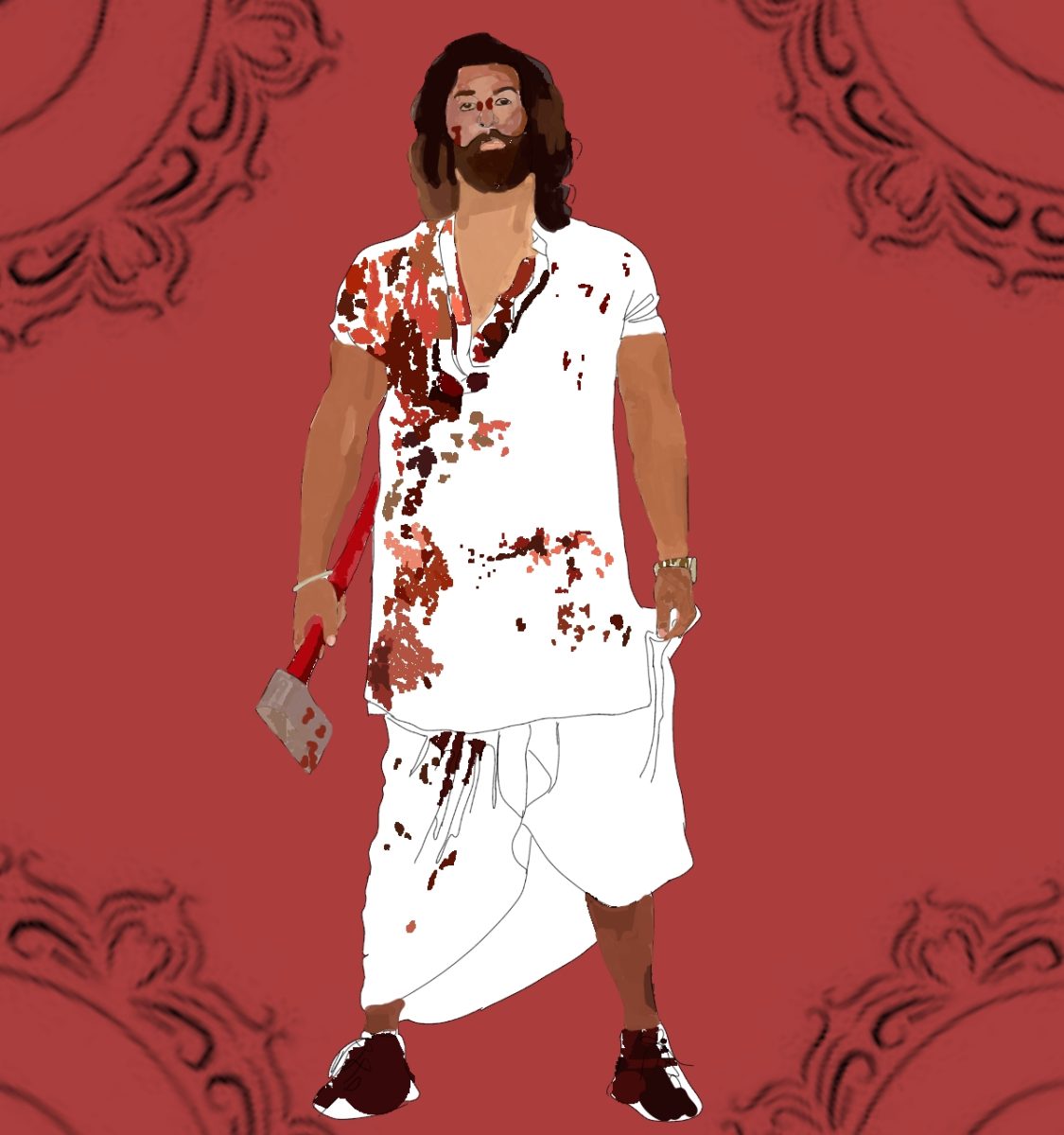

A majestic-haired machine of masculinity hacking down dozens of masked goons while his supporting cohorts, instead of aiding him in his slaughter, stand back to sing an anthem of savagery… is not something western audiences often see.

At the same time, a laid back exposition for a star-studded cast set in a grand mansion with screenplay akin to 1972’s The Godfather is not something Indian audiences are used to either.

Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s film, Animal, succeeds in offering a cinematic experience that dares to go beyond what both audiences expect and even accept. Yet, while its desperation to prove its inventiveness comes through in some parts, others fall completely flat to the same tropes and pits that have plagued Indian cinema for decades.

The premise is an intense drama surrounding the unconditional love of a son for his father who is wealthy, busy, and lacking in time to give little Vijay. In standard Bollywood fashion, these familial emotions carry the majority of the story thematically, even if the plot itself seems to eventually go off rails.

The film follows Ranvijay (Vijay) Singh, played by Ranbir Kapoor, and depicts his life story. Vijay grew up idolizing his father, a rich industrialist Balbir Singh, despite his father’s emotional unavailability towards all members of his family. Determined to step in as the ‘man of the household’ Vijay adopts a toxic personality and spent his time beating up college students, bringing firearms into classrooms, and complimenting women on their “big pelvis”. However, this infuriated Balbir; dreading his son’s behavior, Balbir kicks his son out. Vijay and his wife immigrate to the US where they raise two kids. Vijay is prompted to return to India upon an attempted murder on his father. The rest of the movie follows Vijay as he balances protecting his family and avenging his father.

Throughout this plotline, Ranbir Kapoor’s character Ranvijay Singh is portrayed as impulsive and animalistic, but still intellectually and emotionally complex. Ranbir Kapoor delivers a career-defining performance that is as awe-striking as the background music that scores it.

For context, the vast majority of songs in Indian popular culture are derived from films, as standalone albums are not as common as in the West. So for a project this massive, legendary singers and composers like Arjit Singh and Pritam collaborated for a truly iconic collection of tracks, ranging from a ballad of fatherly affection to a visceral anthem that worships barbarity.

In fact, the consistently stellar music feels out of place at times, especially when the plot grows deranged in the third act.

And deranged is an accurate way to describe many events in the film, ranging from Vijay’s inability to die and the Hitler references, the audience is sure to classify the film as so.

There is a fight sequence that separates the two halves of the movie, and it is a pure, unfiltered adrenaline rush that I will compare to a hypothetical live-action anime sequence if it was actually fast-paced and stylized in all the right ways. It’s brutal, deranged, and awesome… as a standalone set piece!

So it is a shame that it serves to support the same flawed themes the movie forces onto the screen.

An argument exists that, at its core, Animal intends to decode a ‘alpha male’ and address how one is essentially created by exploring themes of relationships with high expectational ties and emotional neglect. This would explain the exaggeration of the stereotype in the film, which makes the audience question why Vijay turned out this way.

However, our protagonist, who feels the need to constantly remind everyone about the “alpha” male that he is, says and does things that come across as culturally insensitive for the sake of sensation. While his character does revolve around being emotionally overloaded, when paired with Bollywood’s elevation of its main characters, the film uses that as justification to elevate his toxic traits. His lies and scandals are startling, deranged, and egregious in a way that attempts to put the audience in his shoes but almost provokes the audience to disagree with the film.

The film pushes the audience to an almost uncomfortable level of hysteria when the protagonist brings a gun to school to save his sister from bullying. From a character-centered viewpoint, this is a choice to heighten our so-called hero’s extremism. But looking at it from ANY other angle, it’s a rehash of obnoxiously glorifying violence when it comes from the character we’re meant to root for: something Bollywood is iconic for, but also something it gets wrong most of the time.

The South Indian director Sandeep Reddy Vanga, controversial for his depictions, and arguably glorifications of toxic masculinity, teamed up with some of Bollywood’s biggest actors to create Animal.

Vanga is known for his ‘macho male’ movies and his constant depiction of men with anger issues. Animal followed two prior releases from Vanga – Arjun Reddy (2017) and Kabir Singh (2019) which have been claimed to be misogynistic. Vanga fears no backlash, in fact, he challenged his audience that he will get more backlash from Animal then Kabir Singh.

Many have noted that the movie’s Vijay reflects Vanga’s ideologies immensely. Responding to backlash to Animal, Vanga has called his critics “illiterate and uneducated” and in an interview Vanga defends violence in a relationship saying, “if you can’t slap, if you can’t touch your woman whereve you want, if you can’t kiss, I don’t see emotion there.”

These comments raised concerns among audiences, however some say that Vanga’s daringness to speak on such a complicated and raw topic is admirable. Supporters defend Vanga, claiming that he represents many relationships across India through his film and brings them into the spotlight, opening a conversation surrounding domestic violence. However, it is important to note that, as confirmed through Vanga’s commentary, the movie glorifies this violence and paints it as something that is romantic.

Despite whatever message Vanga intended to deliver to his audience, ultimately, Animal glorifies and facilitates violence. By creating a storyline in which the protagonist is excused for his violent and misogynistic behavior, audiences are not receiving an “authentic” representation of how the world works but rather told to find this behavior charming.

When our flawed “hero” justifies his misogyny, the film does so too! If the movie was structured to portray the downfall of a man whose emotional highs ride off of violence and sexism, then all the controversial scenes depicting scandalous sexual tensions and idolized brutality would work to support that inherent line: an unstable man who’s emotional highs serve as spectacle for us, and the consequences as lessons.

But the problem arises when this greed to create something sensational combines with commercializing the film to the stereotypical Indian audience, who are used to larger than life characters being almost deified.

When Vijay brings a gun to school and shoots it at the ground as an intimidation tactic, the largest consequence he faces is a slap from his uninvolved father. Police don’t exist in this world, and neither does law. Anyone who questions why seems to leave with the same unsatisfying answer: they’re all filthy rich so it doesn’t matter!

The ambition is there. To create a modern emotional epic on a grandiose scale that reminds us of our adoration for spectacle. As far as technical values go, the cinematography, color grading, and camerawork is top notch. But like Avatar: The Way of Water showed us, spectacle can only take you so far.

Creating an emotionally unstable war machine and fueling him by his obsessive love for his father is intriguing on paper. Flawed characters make for some of the best stories. But this movie, from its conception to execution, revolves around commercial appeal among Indian audiences. And when directors try to experiment within that sphere, they need to be more careful about not letting inherent flaws of that formula stain the otherwise stellar cinema, like it does here.

A cinematic experience is a culmination of countless aspects, which can, and more often than not should, be judged separately. Because a film isn’t just the director and actors, but also the camera crew, technicians, visual effects artists, screenwriters, and a slew of other behind the scenes roles.

So it’s a shame that Animal is so morally bankrupt, because it presents some of the best performances I’ve seen in an Indian movie, paired with instantly memorable music, and setpieces that last with you long after the credits roll. But unfortunately for Animal, this is a case where the sum is not greater than its parts.