In today’s fast-paced, tech-driven world, the traditional image of the nuclear family: one parent working, the other nurturing at home, is fading fast. Replacing it is a more fluid, collaborative, and often financially pressured model, where both parents work, both parents, and both strive to maintain structure in an increasingly unstructured society.

Parenting today often extends beyond the home and into the digital world. While many parents remain deeply committed to being present and hands-on, there’s now an added layer: managing an online identity. Whether it’s sharing family highlights on social media or simply documenting daily moments, parenting has become, for some, a public-facing activity. A study from the University of Central Florida found that parents who frequently post about their children online are more likely to adopt permissive parenting styles and introduce their kids to social media at younger ages. These posts often go beyond private circles, entering semi-public or fully public platforms and raising growing concerns about children’s privacy and digital safety.

However, this public parenting, known as “sharenting,” isn’t always the case; it’s true as well that many younger families deviate from the traditional image of a nuclear family not by broadcasting family time, but by sharing responsibilities that were more or less traditionally divided for each person while upholding that value of structure.

Science teacher and father of three boys, John Aister, does not follow the idea of a single head of household.

“Me and my wife are complete partners,” Aister said. “There isn’t just one person responsible for the kids or work. We both work, we both parent.”

His wife works from home while he teaches at school, and together they juggle discipline, childcare, and housework—a model that thrives on mutual support rather than a strict division of labor.

Similarly, business education teacher Michael Pero, who also balances a busy family life with his wife and two sons, echoes this sentiment.

“The main thing is support,” Pero said. “We all feed off each other. My wife and I support each other with our jobs and with the kids. Based on the day, we might each have to give more.”

Both teachers were raised in homes with more traditional roles, and reflect on how that style of parenting impacted their childhood.

“Did it make it a better childhood? I don’t think so,” Aister said. “I enjoyed my mom being home, but my kids get to see me more than I ever saw my dad.”

“My parents had guidelines, just like we do now, but the way we apply them is different because the world is different,” Pero said.

Neither one shies away from the word “structure,” in their homes, rules exist—bedtimes, mealtimes, but the approach, rather than being enforced by one person, these boundaries are shaped through shared understanding and mutual respect.

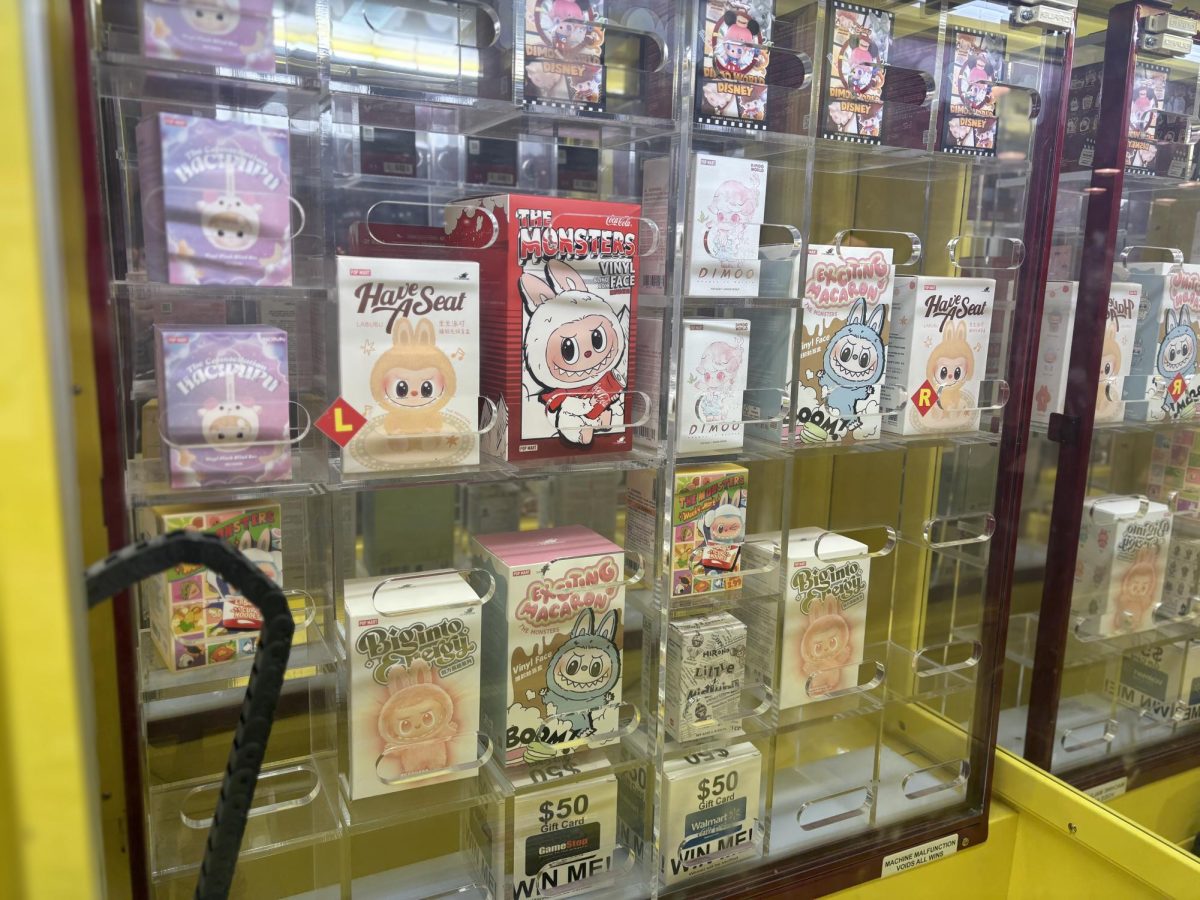

“We have strict screen time rules,” Pero said. “No phone after a certain time, limited apps, and no social media. If we’re not intentional, they’ll default to the device.”

And it’s true. There are children who are growing up constantly on display. There are kids who don’t just exist online, but whose lives are turned into content: daily routines, interactions, even conflicts. This can create a spotlight effect: a performance pressure for parents, but also a boundary erosion for kids, whose private selves are gradually shared for public consumption.

This dynamic often leads to emotional and relational gaps. According to MDPI, when parents are more invested in their digital lives—in their streaming, their online validation, their social personas—the time, attention, and presence once dedicated to play, listening, and guiding can shrink. Kids report feeling unseen or that they must compete with devices. The intimacy of family life risks being reduced to staged photo ops or snippets for stories rather than full engagement.

Part of what’s driving these digital distractions is economic pressure, according to the National Library of Medicine (NIH). The financial landscape today demands more earning, more hustle, more side gigs. A few decades ago, a middle‑class family could often be supported by one income. Houses were cheaper relative to wages. Costs for childcare, healthcare, housing, and utilities were more manageable. Now, unless a family is extremely well off, supporting a household on just one income is often a struggle.

Single households spend a larger share of their income on housing. Even basic consumption (rent, utilities) eats up a bigger piece of the pie when there’s only one earner. Inflation is eroding what income gains there are; many households report feeling “tapped out” despite slight increases in median income because costs (housing, childcare, healthcare) keep rising faster. Simply put, it’s no longer viable for only one person to work and support the family financially as it once was.

These pressures can push both parents into more gratuitous, visible, sometimes performative, public spheres (social media, content creation) to relieve the many roles they have to juggle. The consequence: less downtime, less quiet togetherness, fewer uncurated hours.

When parents are stretched thin financially and emotionally, children often end up raising themselves more than we recognize. Some of the ways this gap expresses itself, like self‑soothing with screens, where kids turn to devices to fill the emotional or time void, and losing unplanned moments—like play, casual chats, or even boredom— can mean missing out on chances to build creativity, resilience, and character. But if parents are busy documenting or performing, those moments disappear.

Society is changing fast. The streaming camera never blinks. Work demands never fully stop. Costs spiral. In that whirlwind, families risk losing the spaces between the moments — the quiet, unfiltered, messy but beautiful stuff.

But building a family isn’t lost in the digital world we now live in. It takes a bit of effort, but it’s still very possible, consciously unplugging and choosing to live in the moment rather than broadcasting every moment, as well as sharing responsibilities with each other. This approach marks a shift from past family dynamics, where roles were more rigid and routines often revolved around a single head of household. In many traditional nuclear households, time together was shaped by structure, but not always by presence. It reflects a move toward intentional togetherness, rather than simply fulfilling roles.

“You just have to be intentional,” Aister said. “Set expectations, set boundaries. It’s harder now, but that doesn’t mean it’s impossible.”